The physical therapy profession and U.S. armed forces have a long and collaborative relationship, one that includes a formal partnership with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Following are a few accomplishments of our women and men in uniform.

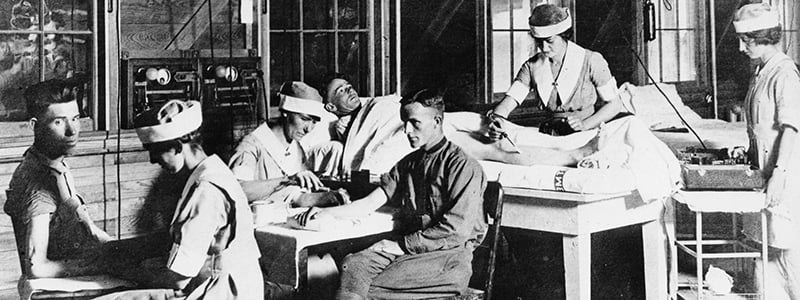

The military introduced the country to physical therapy.

Credit: U.S. Army Photograph.

On April 16 1947, President Harry S. Truman, posing here with Major (later Col.)

Emma Vogel, far right, and other senior officers, signed Public Law 80-36,

establishing the Women’s Medical Specialist Corps (WMSC) in the U.S.

The first physical therapists were reconstruction aides (“re-aides”), civilian employees of the Medical Department of the U.S. Army during World War I who rehabilitated injured soldiers and taught them how to adapt to everyday life after injuries and amputations.

After WWI’s end, as the military cut back on the number of aides, the first physical therapists took their knowledge to the civilian population, working for the U.S. Public Health Service, industrial accident clinics, orthopedic surgeons’ offices, hospitals, and schools for children with physical limitations.

The U.S. Army was key to the process of standardizing procedures.

According to Col. Emma Vogel, one of the first re-aides, prior to WWI very few physicians performed physical therapy procedures, which were looked upon with suspicion by many of their colleagues. It was not a defined discipline with clear standards or guidelines, and there was no research being conducted. Vogel, who later became the first chief of the Women’s Medical Specialist Corps in 1947, wrote that as a result of the success of the re-aides, “civilian practice in this field was given a tremendous impetus” and the Army played a key role in “stabilizing and standardizing physical therapy procedures.”

After WWII, thousands of soldiers were treated for amputations, spinal cord injuries, and other injuries. As a result, some hospitals began to specialize in treating specific populations, allowing for study of effectiveness of patient care, including wound healing, prosthesis fitting, gait analysis, progressive resistance exercise, and constant current stimulation. Severe injuries that would have resulted in immobility during WWI now had a much better prognosis.

Some of the first African American PTs were trained at Fort Huachuca.

The success of Emma Vogel’s 1941 War Emergency Training Course of WWII led to the launch of several more across the country, among them the Special Women’s Medical Service Corps Program for African-Americans at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, which was set up in 1943 to serve the all-black unit. Some of the first graduates included Edythe F. Bingham, Ruth R. Jones, Bernice P. Lockhart, Lillyanne Plummer, Anna L. Rogers, and Valjeanne Taylor.

Military therapists served with honor, even behind enemy lines.

Like their WWI predecessors, WWII therapists served stateside as well as overseas. Metta Baxter, stationed in Italy, was a prisoner of war and received the Legion of Merit. Helen Filbert and Bella Abramowitz Fisher received Bronze Stars for their work in the Dutch East Indies and Okinawa, respectively. Brunetta Kuehlthau and Mary McMillan were captured and held at an internment camp in Manila, Philippines — where Kuehlthau continued to treat patients. These heroes and their colleagues did not gain full commissioned status until 1944.

During the Korean Conflict, several military PTs were recognized for exceptional service, including Major Ethel M. Theilmann, with the Legion of Merit; and Captain Mary Torp and Major Elizabeth C. Jones, with Bronze Stars. During the Vietnam War, 47 Army PTs — including at least three men — treated soldiers, civilians, and POWs in three of the four combat zones.

The military was the first to train physical therapist assistants.

Late in WWII, the Army recognized the need for formally trained enlisted staff to assist PTs in the clinic. Previously, enlisted men were informally trained to help in the clinics but were needed in combat roles. In 1945, the Army approved the first formal program of instruction for the new classification of “physical therapy technicians.”

The military leads the way in direct access and team-based care.

Since the 1970s, the military has allowed soldiers with neuromusculoskeletal disorders to see a PT without referral from a physician, expediting recovery for more minor conditions and freeing up physicians to treat patients with traumatic injuries—which is especially important during combat. Rather than relying on old models of care, the military health system evaluates what needs to be in place for successful outcomes and what resources are needed to achieve them. Military PTs treat patients within a multidisciplinary team of providers, offering a model for the private sector in the shift toward value-based care.

To all our military PTs and PTAs and their families, past and present, thank you for your service.

This post features content originally published Nov. 11, 2019. We’ve included a few updates in this revision, and believe it’s a relevant tribute to our armed forces.